Sometimes, no matter how much will and technical ability there is, factors such as cost, inability to promote and economic hardship can cancel out a real innovation, consigning it to the dustbin of history as just another lost opportunity.

By Vassilis Karikas

Enforcement of regulations to limit pollutants began in 1966 in the US with the National Highway Act. ALFA Romeo, albeit with a small sales share, tried to adapt to the new order, always with the basic premise of maintaining the performance and agility of its engines at the same level as the then standard mechanical carburetor powering. The objective was largely achieved by the injection of SPICA, a specialist company (Societa Pompe Cassani e Affini) which ALFA had acquired in 1948.

However, the ever stricter enforcement of regulations required a change of provision. The immediate response of German giant BOSCH, and its consequent establishment as an OEM supplier for almost all manufacturers in electronic fuel injection, set things on a firm footing, with easier mixture adjustment, lower Nitrous Oxide emissions, and reliability in operation with zero maintenance.

For ALFA's technical designers, however, the solution was not acceptable, seeing it as a necessary sacrifice, and not as a technological advance (the main reason why the first series of the 119 AlfaSei Tipo with the Busso V6 was initially equipped with an array of 6 single Dellorto carburettors). Of course, the perennial problem of financial constraints was a chronic obstacle to integrated Research and Development in the technical departments of the state-owned company, with any innovations not going beyond the drawing board stages. But the opportunity came in 1979, with the largest Research Institute in the country. The CNR (Consiglio Nazionale delle Ricerche) granted the astronomical - at the time - sum of 23 billion Lire to the FIAT CRF (Centro Ricerche FIAT) as capital for the development of technology in the transport sector. ALFA became a subcontractor of the CRF in the field of electronic engine control and hybrid technology development.

With this significant injection of funding, the development of a different electronic management and motor power supply arrangement was possible. One of the key design and operating elements of the company's engines was the multi-plane intake arrangements (Alimentazione Singola), which allowed for greater and wider advance in camshaft timing. Something that existed in carburetors, and was retained in the SPICA (until 1979, when it was gradually replaced by the first BOSCH Motronic systems - at least in the US market).

Since the early BOSCH electronic injection systems used only a central intake butterfly, the comparative advantage was lost, resulting in (among other things) less flexibility over the wider operating range.

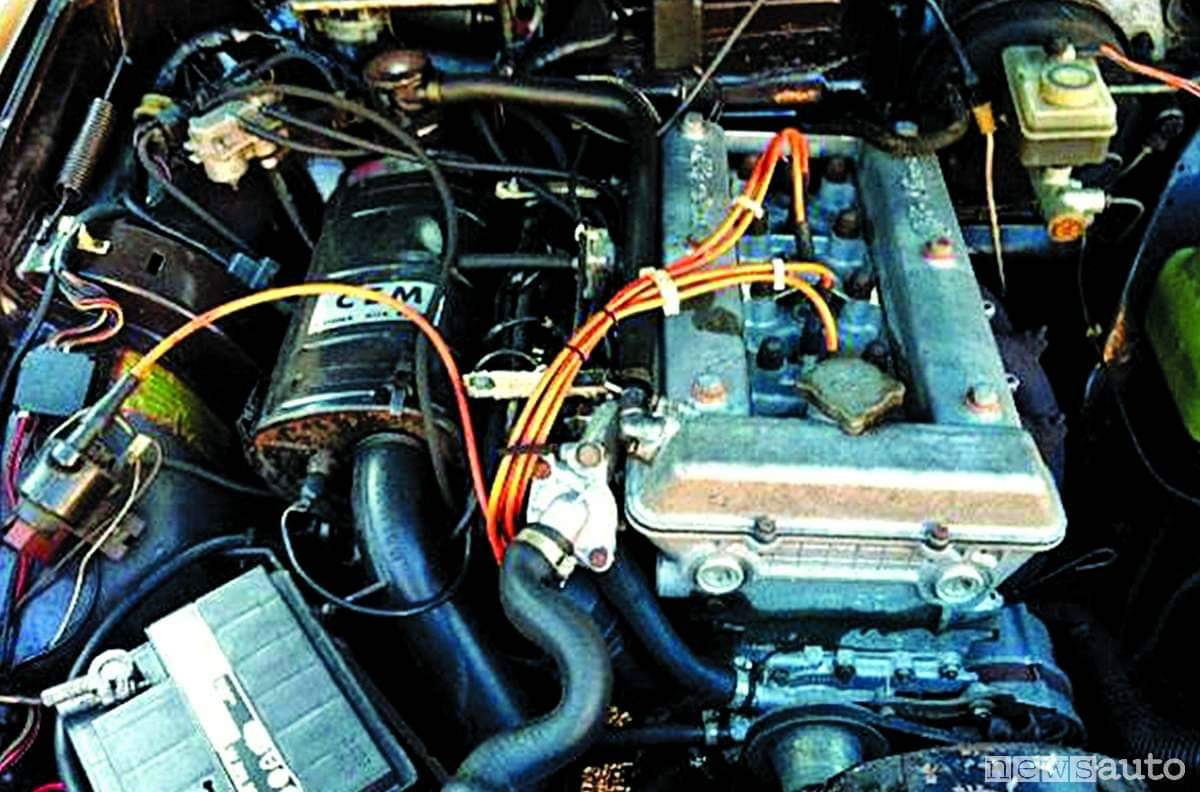

Designed on this premise, the CEM (Controllo Elettronico di Motore) was formed, an electronic device that replaced the carburetors (in the European market, strict emissions had not yet been imposed) with 4 electronically controlled intake butterflies, with the possibility of cylinder deactivation for fuel economy at low load conditions, and a smooth transition to normal power at full load.

It was the first modular spray system of its kind. The state-owned ALFA Romeo, operating under a regime of committees and arterial bureaucracy, managed to technically outperform a niche industrial giant, backed by the almost limitless funds of the entire German automotive industry (and beyond).

The basis of the first application was the evergreen Nord of the Tipo 116 Alfetta, in the 1962cc version. The biggest achievement was the maintenance of the 130hp DIN maximum power output, as in the twin Weber 40DCOE version. The system was piloted with 10 units in taxi form in the city of Milan, for 6 months and 40,000km with careful monitoring and telemetric data.

Since it proved reliable with a measured reduction in consumption averaging 12%, it was expanded, with the production of Alfetta 2.0 CEMs sold to selected customers of the brand in 1983 (the exact number is not known, with most sources converging on 1000 units). The study now focused on the viability of mass production.

However, after calculations, it turned out that the production cost of the CEM-equipped engine was increased by 50% compared to the carburettor version. This was for an annual production of 10 000 units. In overall pricing, the proposed purchase price would have been prohibitive for the car category and the potential audience, so the project was abandoned.

The only final use of the CEM in widespread production occurred in 1985, and lasted until 1987, with AlfaSei's special version for the Italian market only, with a capacity of 2000 cubic capacity, but without the possibility of cylinder deactivation. Around 1500 units were built, until the company declared bankruptcy and was taken over by FIAT Auto SpA in 1986. Subsequent development focused on restoring profits and reducing development and production costs, rather than on engineering innovation and diversity.